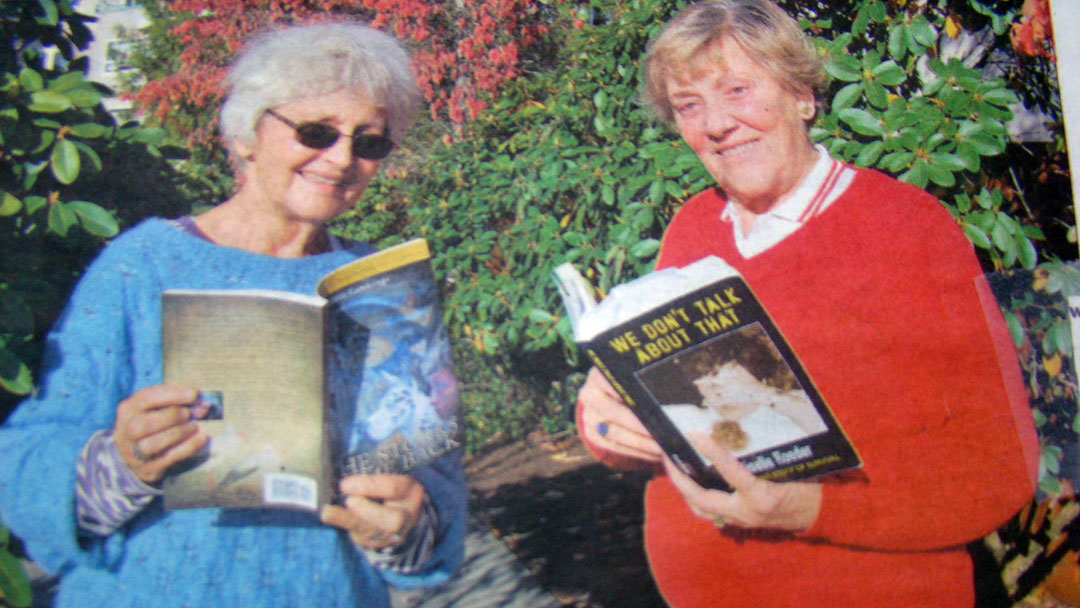

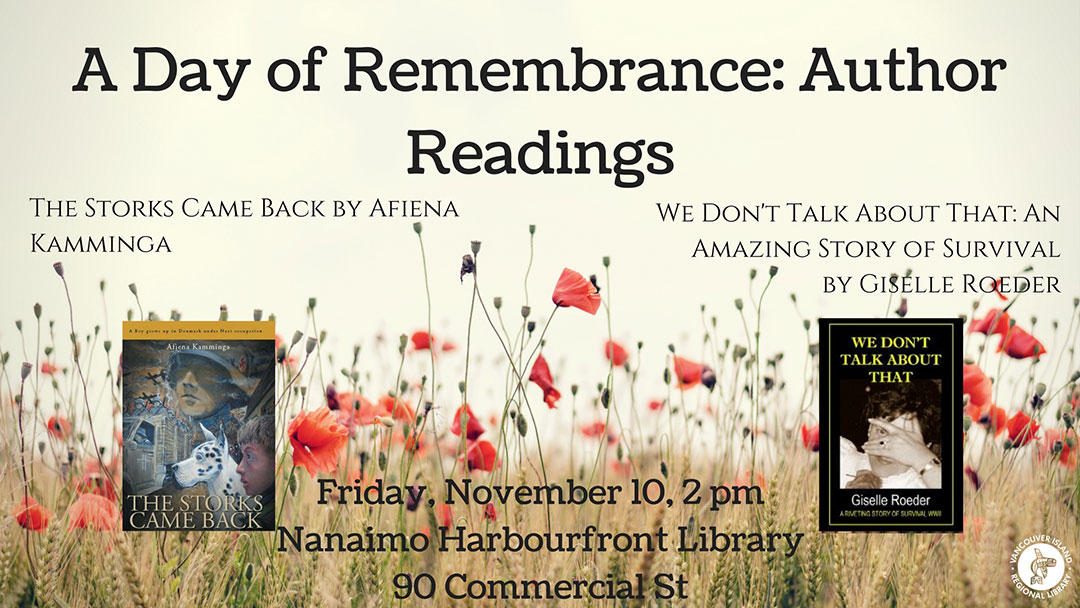

November 10, public reading Harbourfront Library, Nanaimo

Giselle Roeder will be reading from her book of memoirs We don’t talk about that, the author’s childhood memories of being evicted from her home at the end of WWII, and walking with her family for three weeks (together with some 3 million others) plagued by illness and lack of food and shelter, alongside the Russian Army advancing on Berlin.

To find out more about this and other books by this author, turn to her website at giselleroeder.com

Afiena Kamminga will be reading from her new book, The Storks came Back — a Boy grows up in Denmark under Nazi occupation

THE STORKS CAME BACK by Afiena Kamminga

A Boy grows up in Denmark under Nazi Occupation

Why this book?

Afiena Kamminga’s first book-length story for young readers aims to be a cross-over novel to be read by children as well as adults. Young readers will gain a first-hand impression of what it was like for children in a Nazi-occupied country during WWII, to live through those five years of upheaval when children were drawn into the trials experienced by the adults around them. Adult readers of this book will gain a close-up look at everyday life under war and occupation, seen from a child’s point of view.

There are many stories in literature and film featuring WWII battles and those taking actively part in the fighting or in other ways supporting the war effort in a war that (in the literature of English speaking nations) generally takes place ‘overseas.’ There are other, deeply disturbing, accounts of horrific experiences suffered by people, adults AND children deemed unworthy of life and sent to concentration camps to be annihilated in what came to be termed the Holocaust.

But there are far fewer stories in English that tell of everyday life lived by average people struggling through those five years of war, invasion and occupation by Nazi Germany. Many people who lived through these years as children in occupied countries have emigrated to English speaking countries. Each year during Remembrance time in the fall, they are reminded of their childhood years, when war and occupation arrived literally on their doorstep. This book is an attempt to make today’s children aware of the ways in which war affects people’s lives at any age.

Afiena Kamminga is a Canadian author (with roots in the Netherlands). When she learned that the childhood memories of her Danish-born husband ran parallel to her own family history – both families, his in Denmark, hers in the Netherlands, were forced out of their home by occupying German forces – the seeds for this fictional, much of it not truly fictional…, story were sown.

The Storks came Back is the result of their cooperation with valuable input from others who shared their memories of the Nazi occupation in Denmark.

THE STORKS CAME BACK (Summary)

In April 1940 when his country, Denmark, is invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany, seven year old Morten Mors has no idea how his life and that of his family and all other people in Denmark is about to change. School is interrupted. Danish resistance against the German occupiers grows stronger step by step. Morten, eager to join the local branch of the underground resistance movement, is told that he is too young to get involved. Five years later, now twelve, he is still told the same thing. The Resistance is sabotaging railway transports to prevent German troops from heading south to reinforce Hitler’s army battling the Allied on the Western front.

When a German search party is about to discover an explosives stash of the local Resistance — a discovery that would implicate Morten’s family and friends – Morten devises an ingenious plan to save the day. Aided by a friend and his dog he spirits the explosives away against all odds, saving the lives of a number of local resistance fighters.

Visit The Storks Came Back for more details and purchase options

Taking aim at civilians in wartime

The Storks came Back

Excerpt from Chapter 30, Day of Mayhem

From here he could see far across the meadows, across the railway running through the open grasslands, all the way down to the river and the clustered houses of the village on the opposite bank.

Morten narrowed his eyes. In the distance was a tiny plume of grey smoke moving toward them, hidden by trees now and then. Minutes later he heard the chugging and puffing of a steam locomotive. In another minute the train had appeared. No longer obscured by willow and aspen, it pulled out into the open meadow. It was a long train, rolling by slowly. Another refugee transport, Morten supposed. Each wagon was marked on the sides and on top of the roof with a large red cross painted on a white background.

He tilted his head to listen closely. Was that the drone of airplanes in the distance? He squinted against the sun, aware of his heartbeat quickening. No mistake. A half-dozen fighter planes came skimming over the river valley!

Morten stood on the road unable to move, though fully aware that he ought to run for safety.

The next instant, six Allied fighter planes swooped in over the railway. They made a low pass, turned and came back with guns blazing, strafing the entire length of the train. The steam engine exploded in a cloud of steam and smoke. All along the line of wagons, doors flung open and hundreds of terrified, screaming people tumbled out. They raced across the meadow up toward the road where Morten stood nailed to the ground. The planes returned a second time to fire on the scattered people in the meadows.

At last Morten came to his senses. “Snap, come quick!” They ran to the nearest culvert under the road.

Morten flung himself down and squeezed inside, pulling Snap with him to crouch in three inches of muddy water. The planes came back three more times strafing the meadows as well as the road, before heading west. Relieved of spare ammunition they would indeed have an easier time crossing the sea back to Britain.

He gagged. Those pilots and gunners could not have overlooked the red-cross markings on the roof of the train. And when they swooped down a second and third time to strafe the fleeing people, they would have been able to clearly see the ragged civilian clothes of these refugees. They must have known the train carried no enemy troops.

Targeting civilians during a war is distressingly common

By Hans Larsen

(The German Luftwaffe strafed refugees in Belgium and France, the Russian Army targeted civilians in Germany and the Danish island of Bornholm, and I witnessed, at age 10, the RAF strafing refugees in Denmark)

On rainy days we, children, fought spirited campaigns on the living-room floor with our tin-soldier armies. Battle casualties fell over, got back up and continued to fight another round. There were no civilians in our games.

Then one day on my way back from school during the Second World War (by then in its third year), I made a shocking discovery. I saw at close range how far our childish rules of war turned out to be removed from the real thing — the war that kept ravaging our country, one of the many occupied by the might of Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

On that fall afternoon I was biking home from school passing by a freshly plowed field. At the bottom of the field, some two hundred meters down from the road, ran a fenced double track railway connecting the nation’s capital, Copenhagen, with Korsoer, a busy ferry harbor. I was about to turn off the road into a bicycle path, when I saw two trains down there on the tracks travelling in opposite directions, coming under attack from Allied fighter-planes. One train was familiar to me, a school-train bringing older children home from the Cathedral School, the high-school located in the town of Roskilde. The other one I recognized as a refugee-train, a string of crowded freight cars marked with red crosses. The fighter planes destroyed the steam engines of both trains in the first attack – one engine crew perished in the hot steam, I found out later. The planes turned and came back barely clearing the windbreaks around the field. By this time hundreds of people were pouring out of the freight cars, climbing through and over the fence and struggling through the plowed field uphill to where I was standing. The planes flew over low, strafing the people in the field. They turned at the end of their pass and strafed the field once more before gaining height and flying westward to their bases in Britain.

Two days later the last of the dead refugees had been buried in the west corner of the field, hundreds of graves marked with white wooden crosses.

This took place in 1943, and it was not the last war act explicitly taking aim at civilians. Shortly afterwards my family was ordered to vacate our home so the German Army could move in – we were forced to move to the other side of the country, the North Sea coast, to live with my mother’s family. In normal times the journey west, including two sea channel crossings, took about six hours. This time it took six days to reach the west coast. The ferries had been ordered away from their regular crossings, to head south to German held Baltic Sea harbors where massive numbers of German refugees fleeing west, ahead of the advancing Red Russian Army, had collected. Each time a ferry arrived and unloaded its cargo of refuges we stood with other Danish travelers waiting on the dock till the ship was hosed down and returned to regular service, ready at last to receive us, hundreds of ‘regular passengers’ scrambling aboard in a mad dash.

I found a spot on the upper deck and watched the next refugee transport arriving at the dock and unloading large numbers of wounded refugees. The walking wounded did their best to carry or drag the seriously wounded on to the dock. I remember wondering if these unfortunate people might also have been strafed by fighter plane gunners seeking an easy target. One fact of warfare had become distressingly obvious to me at age ten – civilians, even those who obviously were, or could not contribute to the enemy war effort, could be subjected to deliberate attack in wartime. For the remainder of the war, and ever after, I refused to wear the knitted red-white-blue RAF- hat I used to be so proud of.

Unfinished business — War and occupation leave many loose ends to tie up or allow to keep fraying

from The Storks came Back, (chapter 44) Feathers and Tar

Morten walked on through the main street toward the village square with the BP gas station, closed long ago. There was a noisy gathering of people at the gas station. Morten heard rowdy laughter, jeering and cat calls. He pushed his bike through the crowd till he could see the old derelict gas pumps. By accident he bumped with his bike against a tall burly man. The man turned around with a frown, changing to a grin when he caught sight of Morten. “Here, sonny,” he said, stepping aside. “You’ve got to see this, something to tell your grandchildren one day.”

With a mounting sense of dread Morton looked at the scene by the gas pump. Four men dragged a disheveled young woman to the rusty bar connecting the two defunct pumps. They raised her arms over her head and tied her hands to the bar. The pump owner came out of the house with a pair of scissors. He held them up to the crowd for all to see, and set to work snipping off the woman’s long dark hair. Morten caught a glimpse of her face, and his heart missed a beat. The woman was Maya, Niels’s sister, who had cleaned offices and apartments for the Germans.

The bystanders roared.

“Take off her clothes and her shoes and whip her out of town,” a woman suggested. “Chase her right out to the border and across, to her boyfriends in Germany,” yelled another.

Two men carrying a bucket between them made their way through the crowd.

“Make way for us, make way,” warned one of them, a big red-haired fellow. “Mind yourselves now! Don’t get too close to the bucket. We’ve got hot tar in here, and we don’t want to splash anyone.”

They set the tar bucket down near the pump, out of reach for the woman’s kicking feet.

“Anyone has an old feather pillow to donate?” asked the red-haired lad.

“Go get it now! Hurry up! Bring on the feathers and let’s start the show!”

Morten jumped on his bike and sped away, back to the checkpoint at the station. “Uncle Holger,” he cried. “Come quick! They’ve tied up Maya Kristoffelsen and they’re going to hurt her!”

He took a deep breath.

“She’s Niels’ sister! That’s no way to thank Niels for helping the Resistance!”

Uncle Holger jumped behind the wheel of the truck.

“Come along, Joern!”

The unwieldy vehicle, with Morten biking behind, forced its way down the main street through throngs of people, bikes and assorted vehicles.

They arrived at the BP station almost unnoticed. All faces were turned to the entertainment at the pump. Suddenly a machine gun blast from the truck sent ripples of panic through the crowd. Many were screaming and others threw themselves on the ground, arms folded over their heads as if seeking protection from strafing. Joern fired another volley high over the roof of the gas station, prompting the last remaining onlookers to hurry away from the pumps.

Uncle Holger released the terrified young woman from the bar. There were splashes of tar on her face, arms and legs. He helped her into the truck. “We’ll get you to a doctor right away to have those splashes taken care of,” he said quietly. “Afterwards we’ll drive you home. I don’t think people will bother you again. But you had better stay home and indoors for a few days. And don’t show up for a while in the village.”

I based the scene in chapter 44 of The Storks came Back, on my husband’s written notes below:

Five years of war and occupation leave a lot of unfinished business

The resistance movement that emerged in Denmark during the occupation years, 1940-1945, developed its own system of justice. Years after the war when I had a summer-job with a fruit growing farm, I became more fully aware of this. One day, instead of going as usual to work in the orchards and berry fields, we were told to clear out a large barn in preparation for the hundreds of guests expected to attend the grand anniversary of Christian (my employer’s father). Christian had been a ‘lay-judge’ for the Resistance during the war. During those years he had been a highly respected member of an underground court that gathered periodically to judge Resistance members charged with minor to serious forms of misconduct, including the occasional mistreatment of people believed – rightly or wrongly – to be Nazi-collaborators.

Although most people tried to keep a low profile under the Nazi occupation, this changed toward the end of the war. After the first week of May 1945, there was an upsurge of people walking the streets sporting homemade Resistance badges and color-coded armbands. Not all of them could claim any notable history as members of the underground movement. Some self-recruited patriots went out of their way to pursue alleged collaborators, especially women said to have had close relations with the occupation forces.

On the day the German surrender was announced in the village we lived in at the time, a sizeable mob of people had collected in the evening around the old BP gasoline station, defunct since the war began (all gas supplies were discontinued at the start of the war). Elsewhere in the village near the telephone exchange the Resistance had put up a roadblock. The man in charge asked some older kids who had bicycles (myself included) to keep an eye out for trouble. About eight o’clock in the evening I heard wild cheers from the mob assembled at the gas station. I biked down to investigate and found a young woman, often hired by village residents to clean house – including some that housed German Army officers – who was clearly in big trouble. The woman, pregnant with her third child, had been hoisted up strapped to the metal bar connecting the two ancient fuel pumps. Her clothes had been cut away and they were shaving off the hair on her head and elsewhere on her body to prepare for the coating of red metal (notoriously toxic) lead-paint they intended to give her.

I raced off on my bike to the road block for help, and was soon headed back to the gas station riding on the hood of our tank – and old truck secretly armored by the local blacksmith with sheet metal plates. We reached the cheering mob just as they started to cover the helpless woman with lead-paint. Our truck driver sounded the claxon. The gunner beside him fired a machine gun volley in the air, causing the mob to scatter. The victim was released and rushed to the doctor’s office for a thorough paint-removal job. Though she felt pretty sick for a while afterwards, she suffered no lasting effects from the paint. She continued to live in the village, supporting herself and her children with the aid of social assistance and cleaning jobs for a number of households that were willing to hire her.

This sort of thing didn’t occur only in Denmark of course. Similar, or worse, treatment of collaborators – real or perceived – took place in other European countries liberated from German occupation.

The following summer I traveled with a group of other young people to Norway. The trip was organized by my uncle and his Norwegian wife. During our stay in Norway our group was hosted on a farm in Telemark, which belonged to my aunt’s sister.

This sister’s husband, unemployed during the time of German occupation in Norway, had volunteered for a factory job in Germany (to avoid being rounded up forcibly with other unemployed and shipped off to Germany as forced laborer). He survived the hardships and bombings of his workplace in Germany and returned home to Norway after the war had ended – only to find that his home village refused to accept him.

A local committee appointed to evaluate his case and a few others, decided that this man, although he couldn’t be rated a war criminal, had been a willing collaborator with the enemy. Many wanted to chase him away from the village and out of the region altogether. In the end they compromised by allowing him to remain in the area, though not in the actual village. He was free to live in solitude up on the mountain in a hut that belonged to the farm. There he was expected to make himself useful by cutting lumber and firewood on behalf of the farm and taking care of the farm’s cattle brought up to the high pastures for summer grazing. He was entitled to receive food and other needed essentials from the farm in return. These would be left at a certain gate halfway up the mountain. He wasn’t allowed to have any face to face contact with other people, and later we heard that he only lasted up there a few more years.

The horrors of war go far beyond the direct impact of battle and bombardments.

Hans K. Larsen

Excerpt from chapter 7 of ‘The Storks came back’

Bodil winced.

“Aw, let’s not bother with Derdo and Laila. All those little girls want to do is to fly back and forth on their swings, doing that silly little chant about Derdo and Laila, Lassiman, Suomi, Finland, over and over.”

Mrs. Poulsen looked up over glasses. She sent Bodil a glance of disapproval. “That little chant of theirs,” she said, “is all these poor girls have left from their life back home. After the Russians invaded Finland, their parents decided to send Derdo and Laila to Denmark to be safe from the fighting in their own country. And before they sent them away, the parents made their girls remember these words by chanting them over and over again. This way they won’t forget who they are and where they have come from.”

Bodil said, “But why can’t they play by themselves in Mrs. Olsen’s garden? They’ve got that nice swing set put up for them on the lawn.”

“Shame on you, young lady, for having a short memory,” Mrs. Poulsen said.

”Remember, when Mrs. Olsen took in these refugee girls, she asked you to come over to play with them? Feel free to come over as much as you like, she said. That’s how you can help them to feel at home here.”

“But,” Bodil said, “I never promised to play with them every day!”

Morten said quickly. “Why don’t we play with the girls from Finland tomorrow?”

“Then we can’t play at all in the hayloft tomorrow,” said Bodil. “Remember how upset they became that day in the cow-barn, when we heard those bomber planes flying over? Remember how they stormed out the door, looking up to see where the planes were going, and screaming, covering their ears with their hands. They thought we were about to be bombed.”

“All right then, we’ll play with them in their garden tomorrow,” Morten said. “They’re not afraid of planes as long as they can see where they’re headed.”

“Poor things,” Mrs. Poulsen said. “They must’ve been terrified when their home town was bombed. I suppose they and their parents were hiding in the cellar and they couldn’t see out, and they had no idea whether the planes were coming for them.”

Derdo and Laila — notes that inspired part of chapter 7 of ‘The Storks came back’

The two Finnish girls were younger than the rest of us kids. They were fostered out with our neighbours while their parents in Finland fought the Red Army invading their country. Hosting refugee kids from countries involved in the First World War was routine in some smaller countries of Europe that had succeeded in maintaining neutrality, offering safe havens to children endangered by war elsewhere. During and after WWI our community hosted ‘Wiener-children’ from Austria, and later from 1939 and onwards, Finland was forced to send large numbers of children to safety in Sweden and Denmark.

Although they learned to speak Danish in no time, Derdo and Laila played mostly with each other, rarely with us. When they did come over, they went straight for our double swing-set. Swinging back and forth in unison, they chanted “Derdo and Laila Lassiman Suomi Finland,” over and over. We understood it was their way to hang on to their identity and origin.

Soon afterwards we, local Danish kids, became refugees in our own country when the Wehrmacht (German Army) confiscated our homes for their own use.

Years later I attended an international conference in Helsinki. On the first conference-day, Finland’s National Bank invited participants to an elaborate reception in late afternoon.

I arrived late, and everyone sat politely eying the food without sampling, waiting for the bank director’s speech. I chose a vacant chair between some young Americans and three young Finish women who worked at the reception counter. Soon the conversation drowned out the chords of Sibelius’s Finlandia. Two of the women began to tease the Americans, pretending to give good advice about where to go for dinner. “No better place in town, they said, then than TFC near the Hilton Hotel. I struck up a conversation in (my best, imperfect) Swedish, with the third Finnish woman at our table, asking her if Lassiman was a common last name in Finland. I told her about the little refugee girls of my childhood. The third woman then turned to the others, talking in Swedish (Finland is, or certainly was at that time, a bilingual country, using both Finnish and Swedish as official languages). She told them that I understood they were having fun fooling the American guests about dinner options in town.

The two immediately changed their tune, suddenly dispensing excellent dinner advice, and the conversation turned to the hard recent history of Finland, first having a war with Stalin’s Russia foisted upon them that left them war-torn. Subsequently they were forced to pay (forced by Russia and its western Allies!) massive reparations to Soviet Russia.